Ever sneezed more in your office than at the bus stop?

Welcome to the great indoor irony, where escaping outdoor pollution doesn’t mean escaping pollution at all. We close our doors, roll up the windows, and turn on the AC… not realizing we might just be marinating ourselves in invisible toxins.

For years, “public health” in Nigeria has been synonymous with handwashing campaigns, vaccination drives, or cholera control. All crucial, yes — but here’s the quiet truth: we’ve ignored the air inside our own walls.

The Air We Don’t Talk About

Take a walk through a typical Nigerian city:

Generators humming behind every building, air fresheners masking odours, mosquito coils burning nightly, and poor ventilation sealing it all in like a tightly packed puff-puff bag in our air-conditioned offices and rooms.

Now imagine inhaling that mix for 8–12 hours daily in offices, schools, hospitals, or even homes. That’s not “fresh air.” That’s a cocktail of carbon monoxide, Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), mould spores, bacteria, viruses, and microscopic dust — all invisible, all active, and all quietly ruining lives and families.

The results?

- Chronic fatigue, headaches, and increased allergies.

- Persistent coughs that refuse to leave and rising cases of respiratory diseases

- Low productivity, and increased financial responsibility for medical bills.

- And long-term, the silent invitation to heart and brain-related illnesses.

Indoor air pollution doesn’t wear a scary face — it hides behind scented candles, plastic chairs, and faulty air conditioners, diverting our focus from the problem.

The Regulatory Blind Spot

As a country, public health laws guiding air quality needs to be enacted to safeguard citizens from the dangers of air pollution especially indoors. We monitor food safety, water quality, and environmental sanitation. But when it comes to indoor air, we’re largely on our own.

We have buildings go up without mandatory ventilation standards, offices cram-in staff with no air quality monitoring, hospitals disinfect surfaces but ignore airborne pathogens floating in the air, and schools? We rely on aesthetically pleasing environment, closed windows and ceiling fans that just circulate stale air faster. Public health policies tend to stop at the doorway yet, that’s exactly where 90% of our daily lives unfold.

The Human Cost (That We Can’t Afford to Ignore)

Let’s make it real.

A teacher spends 7 hours a day in a poorly ventilated classroom; inhaling constant chalk dust, chemicals from marker ink, fumes from nearby generators, poor ventilation, and no air filtration.

A banker, works in an enclosed office with air fresheners and photocopiers humming all day.

A mother cooks in a small kitchen using kerosene, or even gas stoves with no extractor.

Each of them breathes over 11,000 litres of air daily, and almost all of that is indoor air.

So, when we talk about public health, how can we skip the one thing we literally can’t live three minutes without?

A Breath of Policy Fresh Air

It’s time for Nigeria’s public health conversations to evolve beyond just “clean water and sanitation.” Indoor air quality deserves:

- Inclusion in building codes and health inspections.

- Awareness campaigns linking poor indoor air quality to chronic illnesses.

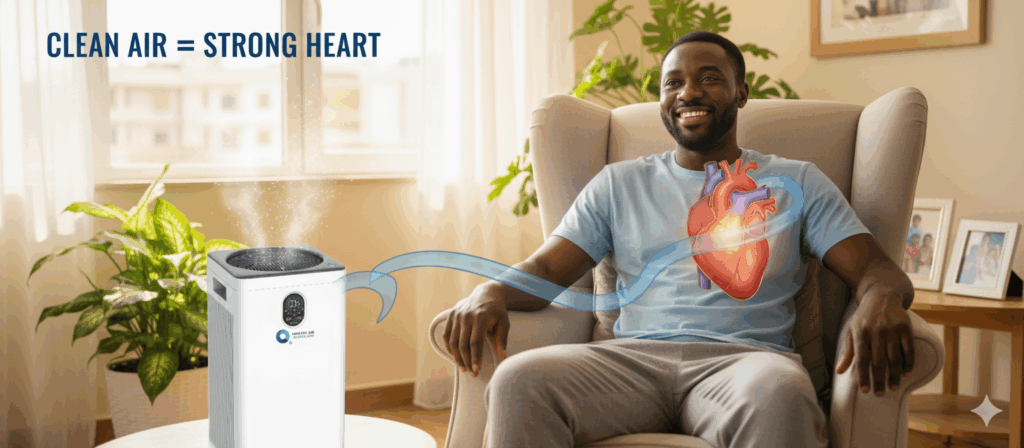

- Adoption of clean air technology in schools, hospitals, and offices.

- Monitoring frameworks to measure and improve indoor air in indoor environments.

Public health isn’t only about treating diseases — it’s about preventing the conditions that create them.

Inhale Change, Exhale Excuses

Clean air is not a luxury for the privileged. It’s a basic human right and a public health priority waiting to be recognized.

Until we start talking about indoor air as part of Nigeria’s public health agenda, we’ll keep medicating symptoms while ignoring the source.

So next time you step into your office and sneeze twice before “good morning” — don’t just laugh it off. That’s your body’s way of filing a public health complaint.

Because when the air we breathe indoors become a public health issue — silence isn’t just bad; it’s deadly